As students are deciding whether to enroll or transfer to stay close to home for Fall 2020, North Idaho College has launched a local social media campaign that also features the benefits of Interstate Passport, including the YouTube video below.

As students are deciding whether to enroll or transfer to stay close to home for Fall 2020, North Idaho College has launched a local social media campaign that also features the benefits of Interstate Passport, including the YouTube video below.

The Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) and the American Council on Education announce a collaboration to help more students with prior learning attain high-quality postsecondary credentials. WICHE’s Interstate Passport Network®, with 46 members in 15 states, enables block transfer of completed lower-division general education among participating institutions based on an agreed upon set of learning outcomes. Basing transfer articulation on the 63 Passport Learning Outcomes (PLOs), rather than on matching specific courses and credits, can help reduce credit loss, saving students time and money and increasing their chances of graduating. The discipline specific learning outcomes were developed by multi-state faculty teams convened by WICHE. Now, ACE will also use the PLOs as a framework in evaluating and recommending college credit for training, certifications, and exams offered by hundreds of providers and major employers.

For over 60 years, using an industry standard process, ACE’s faculty panels have evaluated learning that happens outside of the formal college setting and issued recommendations for academic credit. Going forward, ACE will use the PLOs as a framework for evaluating general education, college-level knowledge and skills embedded in some of these extra-institutional learning opportunities. The specific PLOs achieved by a learner will appear on a new digital transcript on Credly’s Acclaim platform, which institutions can use to translate students’ documented knowledge and skills into courses for general education credit. The PLOs provide colleges and universities with more depth as to what ACE transcript holders know and are able to do as they consider credit recommendations.

“Post-traditional learners face an uphill battle towards their degree goals when institutions are unable to recognize their prior learning. The Passport Learning Outcomes are a great example of a framework that could become the common language for general education to help a wider array of students get the credit they’ve earned for what they know, regardless of where they learned it,” said Louis Soares, ACE chief learning and innovation officer.

Students who receive credit for prior learning graduate at higher rates, which results in more credits taken from their chosen institutions. This benefit holds true across racial/ethnic populations. Today more than ever, all students need flexible pathways to help them restart their careers, resume interrupted educational journeys, or skill up for new opportunities.

“Interstate Passport is a game changer on many levels with the WICHE/ACE collaboration extending its benefits even further than we had hoped,” said Demaree Michelau, WICHE president. “With the significant economic downturn and impacts of COVID-19 having disproportionate adverse impacts on underserved students and students of color, this collaboration has great potential to not only mitigate some of the negative effects of the pandemic, but we also expect that it will go further and improve outcomes for vulnerable populations.”

The Passport Learning Outcomes can serve as a common language describing knowledge and skill attainment that happens in different contexts, building connections between workforce and academia so that students can move more easily between them without losing ground on the journey.

The Passport Learning Outcomes and ACE digital transcripts were developed with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and Lumina Foundation. For more information, visit ACE’s Learning Evaluation and the WICHE Interstate Passport program.

The American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO) has posted information on its website for colleges and universities on what to consider and how to implement changes in policies and practices affected by COVID-19. Institutions are urged to consider long-term implications of any changes made now. Overall guidance suggests the following:

The webpage also includes recommendations on transfer evaluation credit and key questions to consider. In addition, AACRAO invites questions and issues for the guidance team to consider, and provides resources to help institutions navigate the new “normal.” The site is updated regularly.

The University of Hawaiʻi System becomes the third higher education system to join the Interstate Passport Network. Joining Leeward Community College and the University of Hawaiʻi West Oʻahu in the Network are eight additional institutions: Hawaiʻi Community College, Honolulu Community College, Kapiʻolani Community College, Kauaʻi Community College, Maui College, University of Hawaiʻi Hilo, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and Windward Community College.

The Network is a national program of two- and four-year colleges and universities that streamlines the transfer process for students.

“The University of Hawaiʻi System is delighted to join the Interstate Passport network,” said UH President David Lassner. “UH faculty, staff and administrators have been early participants and implementers in shaping the initiative, and after seeing its value all 10 of our campuses are enthused about its potential to assist transfer students and shape our thinking about general education.”

Founded in 1907, the University of Hawaiʻi System (UH) includes three universities, seven community colleges and community-based learning centers across Hawaiʻi. As the state’s public system of higher education, UH offers numerous opportunities through the community colleges to a major global research university that are as unique and diverse as the islands. UH has an overall enrollment of nearly 50,000 full- and part-time students.

Students who earn a Passport, which encompasses lower-division general education and is based on learning outcomes instead of course-by-course articulation, can transfer to a Network institution in another state and have their learning recognized and general education credits accepted. All students in Hawaiʻi who earn a Passport can now more easily transfer to any Network member institution without having to repeat or take additional coursework to satisfy general education requirements.

“With the University of Hawaiʻi System becoming an Interstate Passport member, more of our students’ coursework will be safe-guarded should they need to transfer to any of the growing number of other Network colleges and universities” said James Goodman, Hawaiʻi Passport State Facilitator and Dean of Arts and Sciences at Leeward Community College. “Joining the Interstate Passport Network will also provide another venue for each of our 10 campuses to promote their unique programs and features across the country to students who will be assured that their general education requirements will be fully accepted upon transfer.”

Nearly four in 10 college students will transfer institutions at least once during their college careers, and almost a quarter of those will enroll in an institution in another state, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse. Until now, transferring between schools – especially across state lines – has been made more difficult and expensive by lengthy credit evaluation processes and loss of credit already earned.

“We are excited to welcome the entire University of Hawaiʻi System and its institutions to the Interstate Passport Network,” said Anna Galas, director of academic leadership initiatives at WICHE. “UH has been a key contributor in the development of Interstate Passport processes and operations. Leeward Community College and the University of Hawaiʻi West Oʻahu have been instrumental in paving the way for the remaining institutions to join the Network. Since Interstate Passport launched in 2016, member institutions have awarded over 38,800 Passports. As the Interstate Passport Network continues to grow, we expect to see more transfer students motivated to complete their degrees.”

Even for students who don’t transfer, earning a Passport can be beneficial. Because of its specifically defined learning outcomes, the Passport can become a widely recognizable documented completion benchmark from which employers can gauge a prospect’s skill level and readiness for a job.

These new member institutions bring the total number of Interstate Passport Network institutions to 40.

In late March, Dr. Peter Quigley, former co-chair of the Passport Review Board had an in-depth conversation with Dr. Gretchen Schmidt, Pathways Executive Director for the American Association of Community Colleges. They discussed student transfer and the Interstate Passport in general and how student transfer and mobility are going to be even more important in the immediate future, as students resume studies and schools make plans for the fall semester.

P. Quigley: Where do you see the biggest policy obstacles to transfer and student success with student transfer overall? Where is the accountability finally going to come from?

G. Schmidt: In the coming year or so, I think it will be more difficult to have robust conversations about transfer with any sense of accountability because the enrollment issues are going to be more acute and more profound in the short term, and everybody will be competing for the same students.

This is the conversation I’ve been having over the last six-eight weeks: How do we frame a transfer conversation between community colleges and regional four-year institutions in a time with limited students and limited resources? I think it needs to be about true two-way collaboration built with ongoing sharing of data and some level of accountability. That’s a very different transfer conversation than we’re having now.

PQ: Assuming the short term isn’t short, obviously transfer becomes impossible under current circumstances. One of my complaints about the pathways implementation is that it was state-centric. The current crisis is going to reinforce (the need for) a very regional (national) approach to this. Does Interstate Passport have an increased role in that kind of a profile, in that scenario?

GS: I think the places where you have robust transfer relationships already, those conversations can translate into shared services and successful online transitions and collaborative connections to student support services in a more virtual environment. Holistic supports can be done in a more proactive and productive way for students in those established relationships. In the current crisis I think it’s going to be a larger challenge to start from scratch to build anything beyond very rudimentary course articulation agreements in an online delivery environment. When things stabilize, institutions can then address the necessary student supports needed to have a positive impact on the transfer student experience in a virtual setting.

I do think that more and more the structure of Interstate Passport is vital. As we start to revisit transfer again and talk about mobility in a different way, whatever happens in the next 18 months to two years, the model of basing transfer on learning outcomes instead of general education course articulation is the most viable way to give students the greatest benefit. If we can stop the course-by-course horse trading and base the agreements on learning outcomes, in a way that is faculty-driven and administratively supported with a level of accountability, student mobility will be maximized. That is what Interstate Passport has been all along. Trying to develop individual course equivalencies at scale across states is just not productive. It doesn’t work for students, it doesn’t work at the state policy level—plus it results in these expansive course equivalency guides that are complicated for students to navigate and require constant updating as curriculum changes at individual institutions.

PQ: That’s a great new way to think about what we’ve been trying to do. We’ve had these conversations inside Interstate Passport (leadership) about course equivalency as a real murky area when it comes to transfer.

GS: We have to get over all these stereotypical barriers that the learning outcomes at a community or a regional college, even from a regional four-year to a selective four-year are somehow inferior – who’s to say? If the learning outcomes are the learning outcomes and students are achieving the learning outcomes, and these institutions are accredited by the same accrediting organizations, then I think this goes back to being about territory and enrollment. It has very little to do with students and students’ accumulation of knowledge and demonstration of proficiency.

This should be an academic conversation instead of a process conversation that registrars and admissions offices have. Students too often have the false belief that transfer credits are universally accepted and applied by receiving institutions. This is the acceptability vs. applicability conversation. We do acceptability in transfer just fine, we accept a lot of courses, students have the perception that their courses transfer to the receiving institution, which they do, for the most part. But if they transfer but don’t all apply to meet requirements for their program of study, what purpose is there for the students to take these courses?

We’re not transparent. If we were transparent, we would say, okay you want to take this Psychology of the Law class because you are interested in the content and it applies as an elective at the community college, but it’s not going to transfer and apply at your receiving institution. Knowing this, if you still want to take the course, then absolutely take it! But know, before you take it that the course is only going to be general elective credit when you transfer and will not apply toward your program of study requirements.

That’s fine, I have no ethical issue with it. But we often don’t do that. We just put everything on a check sheet or articulation table that’s very flat and not interactive. So students, particularly those with the least amount of social capital, assume if a course is included in a transfer degree then it’s going to transfer and apply when they go to their receiving institutions. We have to communicate to students more effectively about transfer requirements from the point of entry at the community college.

PQ: If you recall, the data that was so revealing about remediation showed that students who avoided remediation but were tagged for remediation did as well if not better than students who were placed in 100(-level) courses legitimately. Where is the data that shows that the course-by-course horse trading actually has an empirical benefit for students?

GS: My strong suspicion is that it doesn’t exist within states much less across them, and this is about territory and enrollment as we discussed above. The National Student Clearinghouse continues to expand their research and our colleagues from the Aspen Institute, HCM and SOVA are expanding on the work done by Aspen in their Transfer Playbook. This is outside the bandwidth of most institutions’ institutional research capacity and data sharing agreements that don’t often exist among institutions. This is critically important data, and we hope that the organizations I mentioned continue their excellent work exploring such issues.

PQ: You summed it well earlier: agree on the outcomes, transfer the outcomes. How do we start to get people to actually move on the outcomes-based piece and get away from the horse trading and credit hour focuses?

GS: I’ve worked on transfer policy for a long time. Even with statewide accountability it’s a tough nut to crack. Accountability very rarely has a lot of teeth built into it. It’s more of a slightly shaming function than a true accountability function. At the community colleges, we have to be better about not building academic plans in programs of study for transfer students that include courses that do not transfer and apply to their receiving institution of choice. That requires advising in a much different way. You need to know the student’s intent during the on-boarding process, you have to record what program a student selects and make changes in the system if the student changes her mind, you need to know very early on which institution she wants to transfer to, and you have to monitor her progress – if she takes courses off her plan, there needs to be a trigger than explains the consequences.

I do think that Interstate Passport is different because it operates across states, many with rural institutions in places that do not have densely populated areas with large numbers of higher education institutions. Interstate Passport provides students a level of institutional mobility across state lines that they would not have without it. It sets a baseline for acceptance and applicability of credit that provides a level of assurance for students and opens the doors at institutions that the student may not have considered had Interstate Passport not been in place.

We must ask ourselves what lessons from Interstate Passport work can be applied within states and also across states. Even when the presidents and leadership teams across institutions agree to a transfer policy or sign an articulation agreement, the execution is very much dependent on the mid-level leaders and front-line faculty and staff who are evaluating student transcripts. A state, regional or local transfer policy may exist that says the institutions are going to prioritize seamless transfer, but the implementation and the efficacy of the policy often falls to the person who is evaluating the transcript in the department – the dean or the department chair reviewing the application of the program-level courses to the program of study – and that’s where it all can break down.

Dr. Gretchen Schmidt serves as the Pathways Executive Director for the American Association of Community Colleges. Her tenure at AACC began as the lead of the three-year grant initiative funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation designed to create a national model for scaling guided pathways reforms. The outcomes of that project and the work of those original 30 institutions has provided the knowledge base and resources for guided pathways projects across the country. Dr. Schmidt continues to work alongside national pathways partner organizations to develop, refine and adapt resources to assist colleges as they reform using guided pathways as the framework for institutional transformation. She just completed a subsequent national pathways project, called AACC Pathways 2.0, with a cohort of community colleges in 10 states that included urban, suburban and rural institutions. She is considered a national expert on institutional transformation and has led single- and multi-day events at hundreds of community colleges in the last decade. Prior to her time at AACC, she was a program director for Jobs for the Future’s Postsecondary State Policy team. Before JFF, she spent five years in the Virginia Community College System—first as educational policy director, then as assistant vice chancellor for academic and student services. She also served on the staff of state college boards in Arizona and taught undergraduate and graduate courses in Virginia and Arizona.

Dr. Peter Quigley is a Professor of English, University of Hawaii at Manoa and was the University of Hawai’i System Community Colleges’ associate vice president for academic affairs for 10 years, and past the co-chair of the Interstate Passport® Program. As associate vice president, he was responsible for academic program planning, evaluation and assessment; course and program articulation; regional accreditation; federal higher education and workforce development issues, and collaboration with external agencies. He has also served as interim vice chancellor for academic affairs at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa and chancellor at Leeward Community College. His latest book is The Forbidden Subject: How Oppositional Aesthetics Banished Natural Beauty from the Arts.

Melanie Young serves as the Chair of the School of Arts and Humanities at Laramie County Community College in Wyoming and also teaches English. She has led an overhaul of general education at two Wyoming community colleges but is most proud of her work at Laramie County Community College, ensuring that all students who complete the general education block will also complete the Interstate Passport.

The state of Wyoming has only one four-year university so the ability of students at the state’s community colleges to transfer seamlessly – with all academic credits accepted and applied – is critical. The work on redesigning LCCC’s general education program took three years, and it was built around the Passport, in part because less than 10 percent of students achieved the Passport through general education. One challenge faced by faculty and advisors was to better inform students about the Passport and why it is valuable. Before the GE curriculum redesign, “They didn’t understand it or see why they needed it.”

Before developing procedure, LCCC created a philosophy statement about general education that would ensure connections between GE courses and what students were learning, as well as connections to their discipline. LCCC conducted research on what employers were seeking from college graduates and what makes students successful in the workplace – and in life. Nine different teams were assembled for the redesign work, made up of individuals from all over the campus, not just faculty. People who work outside academia, in particular, were able to offer a valuable perspective, and asked questions that really made the difference in how LCCC communicated the philosophy. The diversity of the group made it successful.

As part of the philosophy statement, the teams identified four practices that all GE courses must encompass and which students must demonstrate:

General Education at LCCC:

1. Practices of Exploration, Research, and Problem Solving

2. Practices of Creativity and Innovation

3. Practices of Empathy and Integrity

4. Practices of Communication and Collaboration

The first year orientation at LCCC includes an explanation of these practices and the GE philosophy to illustrate the connections, coherency and value of the GE curriculum.

The redesigned GE program now has a process in place for creating, approving and maintaining courses. Every GE course had to “reapply” to general education. The number of GE classes went from over 150 to 53, and the GE curriculum is not discipline specific. (See link to the General Education Characteristics Checklist below.) Course offerings are reevaluated once a year. Importantly, this process encompasses operational aspects of the college, i.e., facilities, enrollment, and advising as well as the educational piece. And every student who completes GE will earn a Passport.

Melanie was struck by the tremendous growth and understanding she saw among the people involved in the redesign conversations. Everyone began to think about the institution as a whole. The overarching question became, “Does this serve everybody?” The previous process only considered if a class met educational goals.

The process of revamping the GE program also emphasized the value of general education for all students, and the value of the GE program in general. Melanie thinks we need our best faculty teaching GE to fulfill “our promise to students that they’re going to have a great educational experience from Day One.”

The LCCC General Education Philosophy Statement is available here.

The LCCC General Education Characteristics Checklist is available here.

Pass/fail grades may help students during the COVID-19 crisis, but could cost them later

JON MARCUS, The Hechinger Report, Aired on PBS New Hour, Apr 7, 2020 6:02 PM EDT

As with everything else in Americans’ day-to-day lives, the COVID-19 pandemic may significantly affect the transferability of academic credits when students transfer to new institution. A story produced by the Hechinger Report and aired on the PBS News Hour describes how colleges and universities moved to a pass/fair grading system as schools closed doors and began holding classes remotely. But the transfer of academic credits is already at a low rate, and courses graded simply “pass” may not transfer at all. This presents a serious problem for graduate-school bound students who hope to enroll in competitive law, medical and business programs. In addition, thousands of students that have relocated to their home states will likely transfer to their local institutions to complete their degree programs – making credit transfer all the more essential.

Helping Students Avoid Problems with the ‘The Asterisk Semester’

Podcast from Inside Higher Ed [25 minutes]

This podcast is hosted by Paul Fain and features Lila Burke, reporter at IAG; Anne M. Kress, president, Northern Virginia Community College; and Marie Lynn Miranda, incoming provost of the University of Notre Dame, who is spearheading an effort to persuade medical schools to accept pass/fail grades for incoming students (see, https://provost.nd.edu/news/call-to-action/). Colleges and universities have switched to pass/fail grades in the wake of the pandemic and shut-down. Participants discuss the uncertainties faced by students, the challenges of the pass/fail grading system, and how college leaders can and should avoid disruption for students that transfer.

College groups release joint guidelines for accepting credit during coronavirus

By MADELINE ST. AMOUR, April 16, 2020, INSIDE HIGHER ED

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, six major higher education groups have issued a set of principles for accepting academic credit. Drafted by the American Council on Education and signed by leaders of groups representing public, private nonprofit and community colleges, the statement highlights eight practices institutions should follow to best help students navigate the transfer of credit process. Among the recommendations: institutional practices and policies around transfer should be holistic and transparent, institutional decision-making should be swift and definitive, and institutions should recognize the burden students are under during this time of dislocation and uncertainty. Link to full article here.

Creating Seamless Credit Transfer: A Parallel Higher Education System to Support American through and beyond by Recession

By MICHAEL B. HORN AND RICHARD PRICE, Christensen Institute, April 2020

The authors of this new report from the Christensen Institute propose the creation of a parallel higher education system in which third-party credentialing entities would “validate industry-valued skills” acquired and demonstrated by students. Using stimulus funds, this solution to the nation’s higher education credit transfer challenge would move away from institutions and learning equivalency and focus on the accumulation of knowledge and skills and foster seamless transfer without credit loss. The authors present an argument for their proposal based on the decades-long problems in credit transfer as well as the attempt at records transfer and integration in the medical industry ten years ago.

Download the PDF report at: https://www.christenseninstitute.org/publications/credit-transfer/

Episode Seven: Demystifying the College Transfer Process: What Students and Families Need to Know

National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC), Podcast [26 minutes]

This episode is part of the College Admissions Decoded podcast series, which features NACAC member-experts in conversations that speak directly to parents, families, and the general public to help demystify the college admission process.

This podcast offers tips to potential transfer students and explores ways to make the transfer process between community colleges and four-year schools more seamless.

Participants include Janet Marling, executive director of the National Institute for the Study of Transfer Students, and Dayna Bradstreet, senior associate director of admission at Simmons University in Boston.

As today’s college students are increasingly mobile, the transfer process can be difficult because of problems obtaining credit for previous coursework, a lack of adequate academic counseling, troubles obtaining financial aid, and more. And transfer students themselves are increasingly diverse, including military students, older students returning to college after a break, and students hoping to transfer credits from more than one institution. The podcast participants urge admissions counselors to be well informed about credit transfer and pathways in order to communicate accurate information to transfer students. The most important recommendation is for transfer students to be their own best advocate. This podcast provides ways to do that.

Improving the Transfer Handoff: The critical effort to help college students get a four-year degree

By KATHERINE MANGAN, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2020

Focusing on the most common form of transfer — from two-year to four-year colleges—this report analyzes which approaches are working for successful student transfer and provides practical advice on how to eliminate the barriers standing in students’ way. The author discusses why transfer success is so critical, and presents five case studies that illustrate how two- and four-year institutions can collaborate to help transfer students. The report also and also offers a commentary on why community colleges are good for students: they are providing an open door, reaching diverse groups, and fulfilling the nation’s goals.

Transfer Students

The Chronicle of Higher Education Idea Lab, Colleges Solving Problems, 2019

This collection of articles showcases successful efforts to deal with the myriad problems of student transfer and includes essays about the urgency faced by colleges and universities to improve the transfer experience. The solutions are well known: transparency, academic guidance, better orientation for older and/or returning students, and a simplified process.

During the 2018-2019 academic year, Interstate Passport Network members officially reported to the National Student Clearinghouse that 12,786 students were awarded Passports. Students earn a Passport when they have earned a minimum grade of a C or its equivalent in Passport Block courses. Deadlines for reporting Passport Completion and Academic Progress Tracking files for the 2019-2020 year are fast approaching. The Passport Completion file should be submitted by June 15, 2020, and the Academic Progress Tracking file needs to be submitted by August 15, 2020. Submitting the Academic Progress Tracking file by August 15 ensures that the data will be included in the Interstate Passport Annual Report. With the understanding that institutions have made changes to their grading policies due to COVID-19, institutions are encouraged to award students with a Passport if they have earned a Pass/Satisfactory/Credit for Passport Block courses so long as those grades are equivalent to a C grade or better.

The Interstate Passport website and the National Student Clearinghouse have several resources available to assist in file submission.

To learn more about the value of Academic Progress Tracking, read a recent article in the Interstate Passport Briefing here.

By Michael Torrens, Utah State University

A crucial element of participation in the Interstate Passport Network is the reporting each institution provides on Passports awarded and the post-transfer academic progress of students with Passports. Participation in the Passport Network involves a certain amount of trust that the students that transfer into your institution (and who earned their lower-division general education elsewhere) will be adequately prepared to succeed and graduate. Each institution provides data for its Passport student transfers to the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) in cohorts, and NSC aggregates this information and reports back to each institution and the Passport Review Board as Academic Progress Tracking reports. Academic progress details include: Gender (Male/Female); Race/Ethnicity; Age; Low Income (Pell-Eligible as the proxy for low income); Active Military/Veteran; GPA Earned Before Transfer; Credits Earned Before Transfer; First-Generation Student; and Degree-Level (Associate vs. Bachelor’s).

Academic progress reports provided to member institutions, and to the Passport Review Board, provide the assurance that members are fulfilling their expectations. Members of the Network provide detailed, student-level, academic progress data, tracking students for two terms after transfer. In addition to providing details for students that transferred in with a Passport, data for two comparison groups is also provided: 1) students who made the same transfer (from one Network institution to another Network institution); and 2) students who earned a Passport at the recipient institution, but did not transfer. NSC maintains the confidentiality of this data.

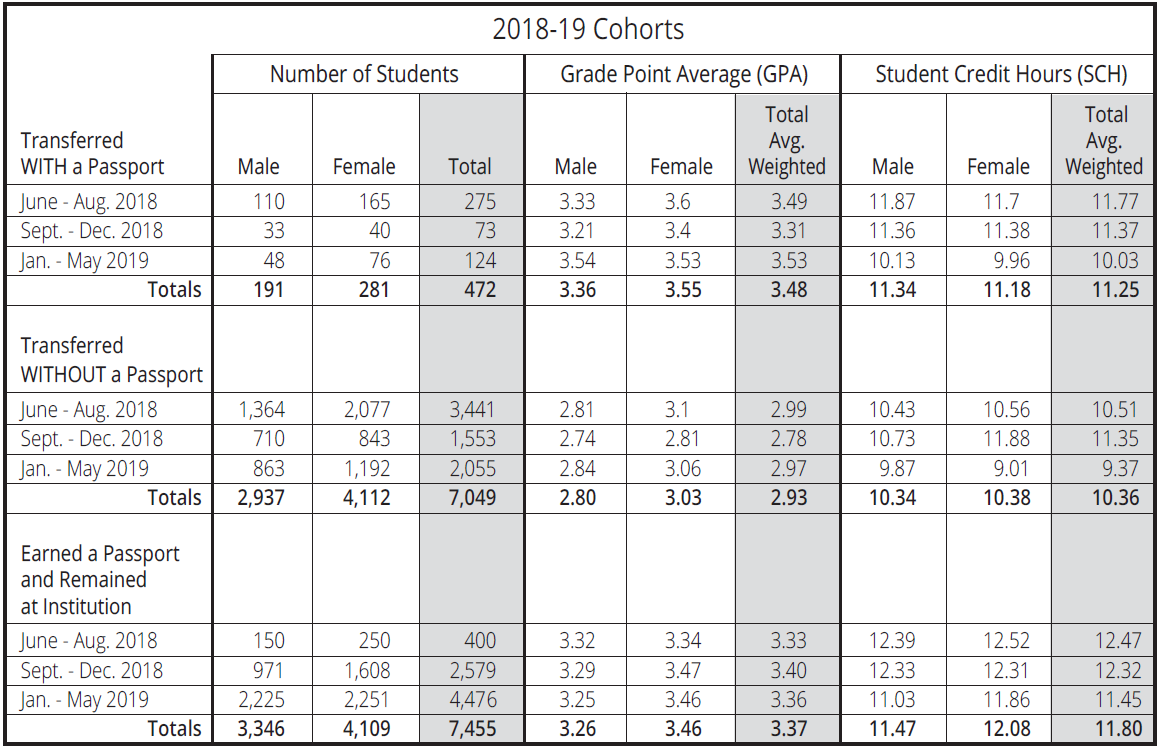

In the third year of Network operations (AY2018-2019), 17 institutions submitted reports for Academic Progress Tracking through the NSC. This is more than double the number of institutions reporting in AY2017-2018, and represents 77 percent of the institutions that reported Passport awards. For the first time, the data provides sufficient numbers of transfer students with Passports to have confidence about the summary statistics provided in many of the dimensions that comprise academic progress tracking. A total of 472 student transfers with a Passport were reported in the three cohorts reported in AY 2018-19 (June 1–August 31, 2018; September 1–December 31, 2018; and January 1–May 31, 2019).

A comprehensive review of the academic progress data reported for AY 2018-19 shows some general trends across all reported dimensions. For the 472 students who transferred with a Passport in AY 2018-19, grade point average (GPA) after transfer was consistently higher when compared to students who transferred without a Passport in AY2018-2019. In addition, academic performance of students who transferred with a Passport was roughly comparable to that of students who earned a Passport and remained at the same institution.

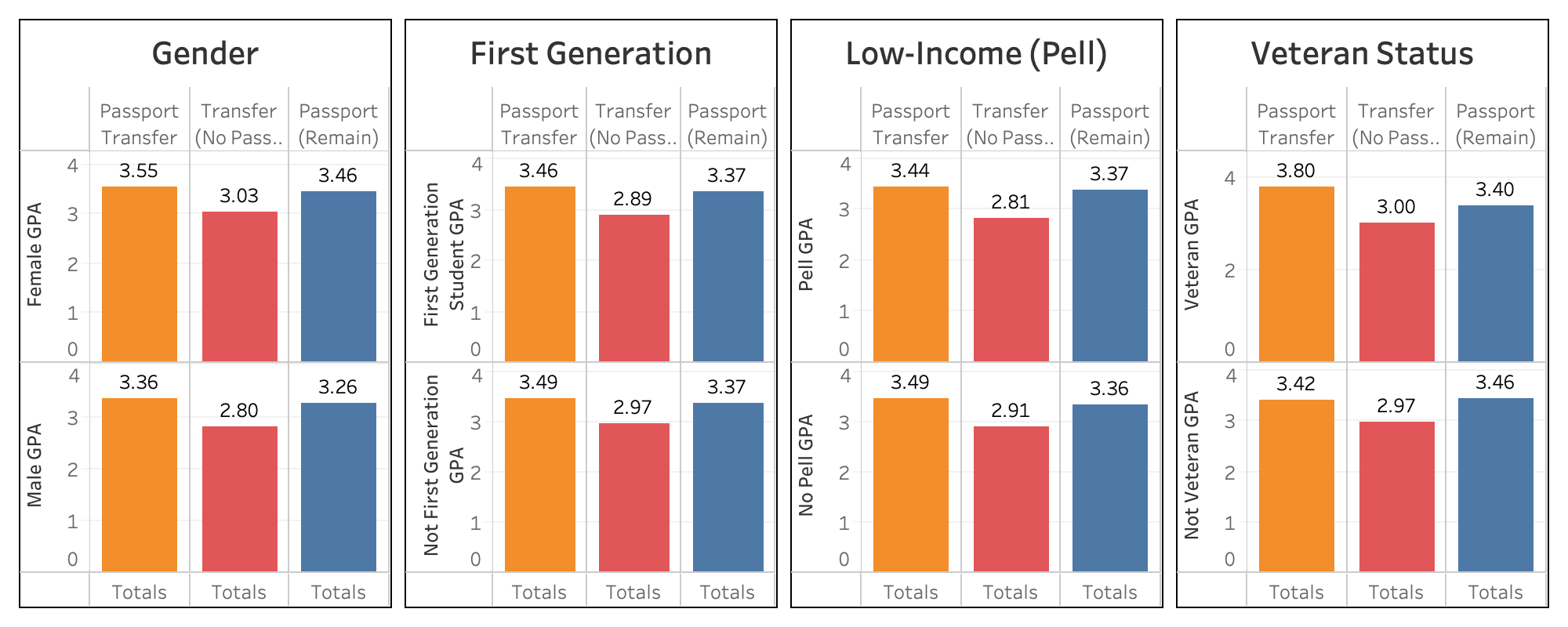

The figure below shows average GPAs, post-transfer, across four

representative dimensions. The results across these four dimensions show

statistically higher average GPAs for students who transferred with a Passport

(in yellow), when compared to the average GPAs of students who transferred

without a Passport (in red), and similar average GPAs for Passport transfers

compared to the students that earned a Passport at the same institution (in

blue).

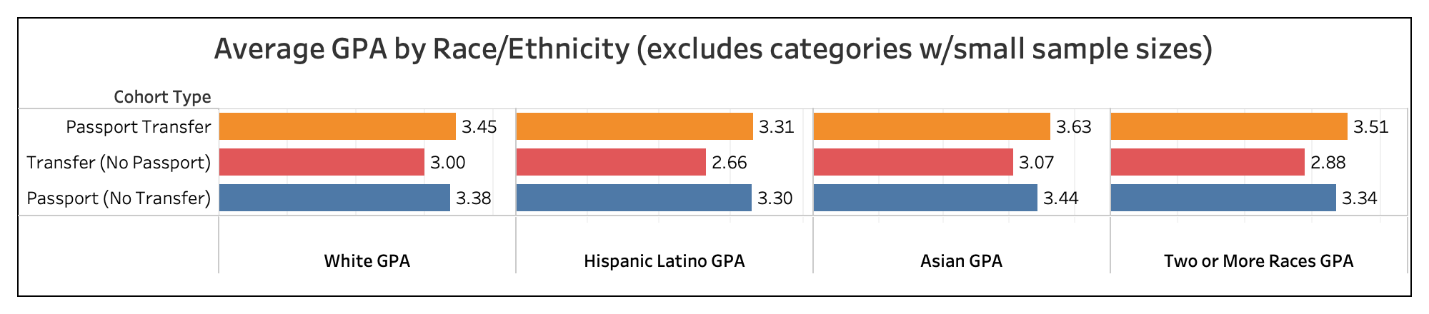

With 472 Passport transfers, statistically valid samples were not yet available across all reported dimensions, particularly for those sub-populations of Passport transfers that are a small percentage of total Passport student transfers. The figure below provides academic progress detail for Passport transfers by race/ethnicity. Please note that the information displayed for Average GPA by Race/Ethnicity includes four categories (White, Hispanic/Latino, Asian, and Two or More Races). In coming years data sets for the other reported dimensions (Black/African American, American Indian/AK Native, Native HI/Pacific Islander, and non-resident alien) will be available as their sample sizes grow large enough to statistically analyze and publish. Average GPA for Passport transfer students was consistently higher across all reportable dimensions of race/ethnicity, in line with the other reported dimensions.

In summary, across all areas of measurement, post-transfer academic progress for students who transferred with a Passport was consistently higher than that of students who transferred without a Passport. The average GPA for the 472 students who transferred with a Passport in AY 2018-19 was 3.48. This compares to a GPA of 2.93 for students who transferred without a Passport, and a GPA of 3.37 for students who earned a Passport while remaining at the same institution. The average number of semester credits earned by students who transferred with a Passport was 11.25, compared to 10.36 for students who transferred without a Passport. These details are clear in the table below, which summarizes academic progress detail by gender.

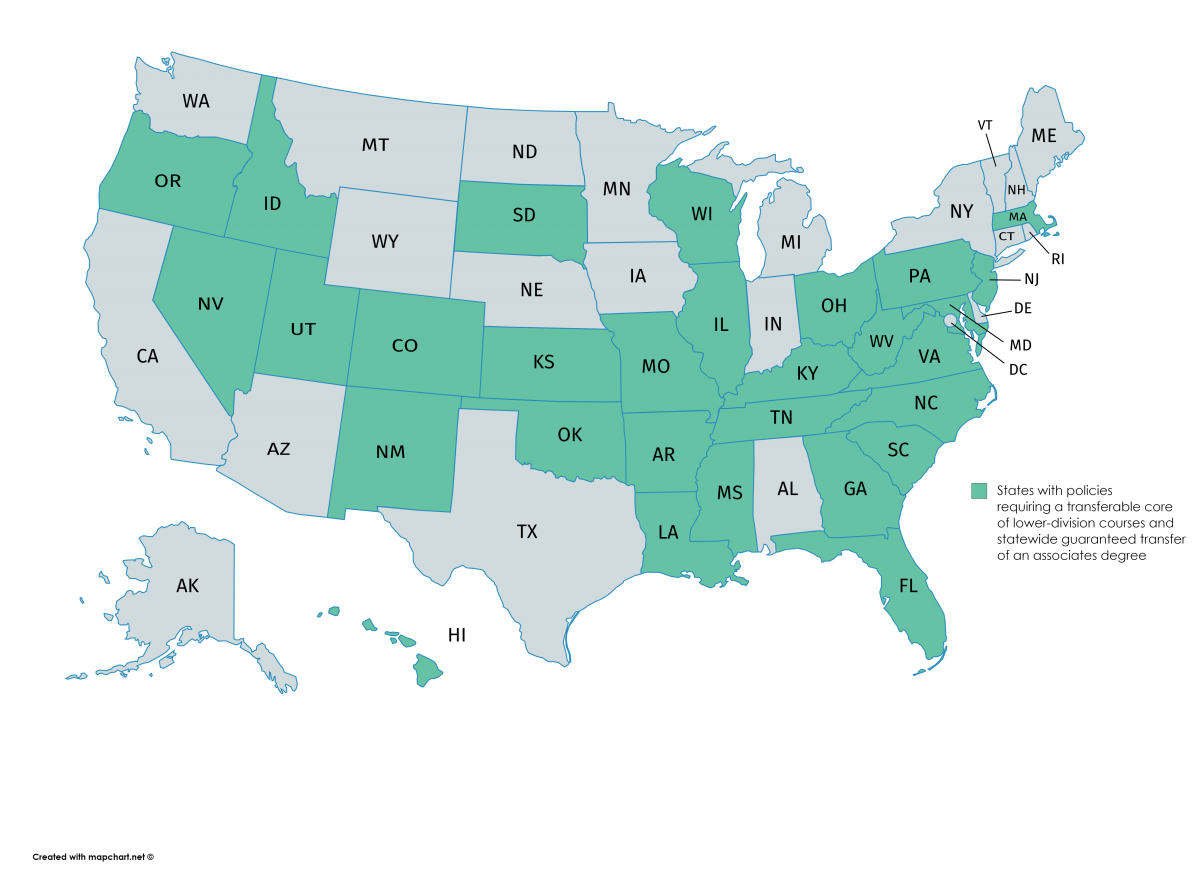

We reported on the Education Commission of the States’ 50-State Comparison: Transfer and Articulation Policies in our last newsletter. This month ECS has released an updated report:

The report notes that many states are continuing to refine statewide transfer policies toward increasing student completion rates.

The report compares all 50 states in four transfer metrics: (1) transferable core of lower-division courses; (2) statewide common-course numbering; (3) stateside guaranteed transfer of an associate degree; and (4) statewide reverse transfer. The document presents tables showing how all states approach these policies as well as individual state profiles.

Now, eight states have policies in all four metrics: CO, FL, ID, KS, LA, MO, NV and TN (Idaho and Louisiana added); and seven states have no policies in the four areas: CT, DE, NE, NH, NY, PR, and VT (Puerto Rico added). The rest of the states have some but not all of the policies in statute, sometimes because of more than one higher education system within the state, i.e., different system policies, or because of non-alignment with the community college system. In many states, even if a transfer policy is not in statute, agreements are in place between specific institutions or systems within a state that permit transfer of lower-division courses, reverse transfer, or guarantee transfer of an associate degree.

50-State Comparison: Transfer and Articulation Policies

Education Commissions of the States, February 2020