ELIMINATING THE FRUSTRATION OF TRANSFER

“The success of this project has depended upon such leadership and dedication from so many, but also because it is propelled by a single clear idea: student success.”Peter Quigley, Ph.D., Associate Vice President, University of Hawaii System

For the student, transferring from one institution to another can be a frustrating process, particularly for students transferring from community colleges to four-year institutions. The process often represents a step back in the forward momentum of their academic path and extra cost to repeat course work.

In fact, the Community College Route to a Bachelor’s Degree reports only 58 percent of transfer students are able to bring 90 percent or more of their credits with them.

These circumstances were at the center of a discussion by the chief academic officer members of the Executive Committee of the WICHE-based Western Alliance of Community College Academic Leaders in July of 2010. The committee suggested that a new transfer framework was needed — one that focused on learning outcomes, rather than specific courses and credit hours. They asked the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) to convene a meeting of the academic leaders from both the two-year and four-year sectors in the Western states to discuss this idea. From that meeting emerged a grassroots effort led by a taskforce of higher education representatives from WICHE’s 15 member states. Their charge: to generate solutions for transfer students who often lose credits, repeat or take additional courses and spend additional money to complete degrees. The taskforce chose the name Interstate Passport to represent the new framework that would allow block transfer of lower-division general education learning across state borders.

As the work progressed on this grass-roots initiative, several guiding principles were established:

- Development of the Passport Learning Outcomes would be led by faculty.

- Institutional autonomy would be respected.

- Quality assurance measures would be put in place.

Defining General Education Block Transfer

Funded by The Carnegie Corporation of New York, the initial proof-of-concept work on the initiative focused on obtaining and evaluating data about the general education core, state transfer policies, the numbers of students who transfer and policy-change processes in each pilot state in order to develop a baseline of understanding. Work during this pilot phase also included identifying nine knowledge and skill areas that would anchor the framework of the Interstate Passport program.

Carefully designed by faculty, registrars, institutional researchers and academic advisors from institutions in multiple states, Interstate Passport’s components address and eliminate the difficulties that confront college students when transferring to other two- and four-year institutions.

After background data was gathered, research conducted, and the framework constructed, the concept for block transfer of lower-division general education based on learning outcomes was put into action. Faculty members from two- and four-year institutions participating in the pilot developed Passport Learning Outcomes (PLOs) in the three foundational skill areas: oral communication; written communication; and quantitative literacy. The next phase of work was launched with an additional $3.6 million in grant funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Lumina Foundation. Faculty members from both two- and four-year institutions worked collaboratively to develop PLOs in the remaining six lower-division general education knowledge and skill areas: natural sciences; human cultures; critical thinking; creative expression; human society and the individual; teamwork and value systems.

Through this process, faculty from the participating institutions acknowledged that their institutions’ lower-division general education learning outcomes in these areas were equivalent to the Passport Learning Outcomes. Institutions are not required to use the same language in their learning outcomes as in the PLOs, but rather, to ensure that they are congruent with the PLOs. With the learning outcomes defined, interstate faculty teams developed proficiency criteria, which are examples only, not requirements, of how students might demonstrate proficiency with each learning outcome. Sample activities come from different disciplines, may span multiple learning outcomes, and cover a range of formats (written, oral, visual, performance, individual, group). Each faculty member develops his/her own ways for students to demonstrate proficiency with the PLOs, but the examples illustrate the expectations of students by participating faculty and provide a context in which to view their own assessments.

Funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation also supported institutions to better prepare for the implementation of the Interstate Passport program on their campuses, including student advising, marketing and communications, and necessary support staff to assist new states and institutions.

The Need for Quality Assurance

Central to Interstate Passport was the need to measure and demonstrate student success. To be awarded a Passport, a student must earn a minimum grade of “C” or its equivalent in all Passport Block courses and/or learning experiences. The architects of the program built in a robust data collection and tracking system that is designed to measure the academic progress of Interstate Passport students for at least two terms after earning a Passport, or at least two terms after transfer. The National Student Clearinghouse was designated as the central data repository. A second quality check is the Passport Review Board. The board, consisting of one member from each participating state as well as transfer, learning outcomes, and assessment experts, is tasked with reviewing results as well as considering issues and challenges raised by states or institutions.

From Regional to Nationwide

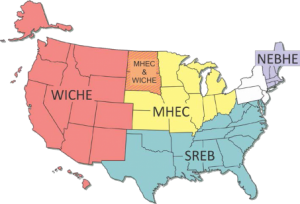

Although Interstate Passport originated in the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education region, it was always intended to be a nationwide program as students transfer across state lines to and from all regions of the country. The second phase of work included expanding the reach of the program by inviting 50 new institutions from states in the other three higher education regional compacts – Midwestern Higher Education Compact (MHEC), New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE), and Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) – to join the program and participate in implementation.