Putting the Way Forward in Context

It has been several decades now since the “field” has moved from a focus on increasing access to a focus on success. Suddenly, it seemed important to say, “Getting students into the system is not sufficient. Getting them through is the point as well.” As a result of this insight, the pathway initiative was born. In a nutshell, Guided Pathways is the not-so-revolutionary proposition that classes ought to be lined up and available in a way that allows students to have access to them in order to get through quicker and more efficiently. Other support services should be deployed along the way as well to ensure no loss of momentum. And now, there is a growing light looming on the change horizon: Success at what?

It’s not just getting students through the system that is the point. The question now beginning to formulate is, shouldn’t there be an intentional connection between academic programs and the world of work? Getting the disenfranchised, the poor through the system is not success unless that experience also yields a dynamic entrance into the world of work. This is the new “transfer” challenge. We used to look down our nose at such a sentiment, saying this sounds like “job training” not “education.” Our job, we used to say, was to build character, build critical thinkers, global citizens, as though such goals should not also equip someone with translatable skills for the workplace.

Slowly and painfully, coming to the surface in fits and starts, is a fundamental reappraisal of the nature, point, and purpose of higher education. Previously, higher education prided itself on being an indifferent monolith where students entered one side and came out the other side all the wiser, erudite, sophisticated and equipped with the information, the tools to change the world and to navigate wisely through that world. A world has emerged, however, that requires more information be acquired by more segments of society. This means education is now seen as a practical necessity, not the right of passage for an elite segment of culture. In a word, education is in the process of being radically democratized. As a result, we have tried to study how students successfully get through the monolith, why it matters and what happens when they do.

With varying degrees of success and impact, accreditation agencies (insisting on learning outcomes), Achieving the Dream (“Look at your data; see how many are losing out in remediation cycles!”), Complete College America (“Deploy game changers top down; make things that work state policy!”) along with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Lumina Foundation and others have all tried to challenge the status quo of higher education, to reshape the success ratios nationwide and the change the conversation.

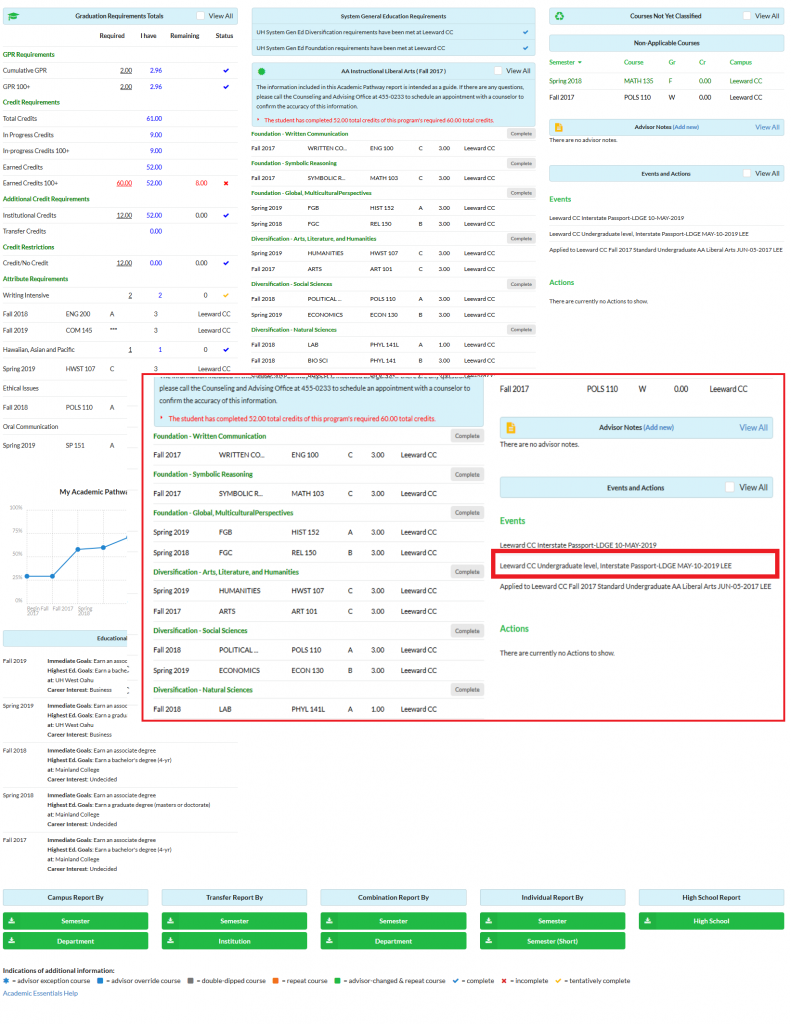

Interstate Passport figures in this context as one of the most impactful and important structural changes in all of these discussions around the change initiatives. Co-requisite and Pathway initiatives are needed critical changes regarding how we orient parts and pieces inside a degree; Interstate Passport, however, is a large-scale initiative that takes on one of the most dangerous areas of student activity: transfer is the cliff students fall over more often than even the data show. Earning a Passport accelerates and propels students forward into the next and most crucial part of their journey towards completion. If co-requisite saves students from the gravitational pull of remediation and if Pathways gives a clear charted path forward, a Passport launches the student journey past the most hazardous of all the traps that exist in the first two years of college: transfer. Many important articles have documented and re-documented this dangerous area. In “Jumping the Chasm,” David B. Monaghan and Paul Attewell, for instance, studied a group of community college students with 60 credits and who are on record desiring to earn a BS or BA. Of these, only about 60 percent successfully transfer to a four-year institution. What happened to the others? Jumping the chasm of transfer seems to be the culprit. The other big story here is that of those who do transfer have the crushing experience of not having their credits accepted. This is a wound that eventually translates into walking away from a system that ignored the work students already had accomplished.

The existence of Interstate Passport announces that the work students have accomplished should count and that it carries significant purchase into any other college program in the area of general studies. General education is, after all, “general education.” Faculty in specific discipline areas in 15 states have validated the fact that there is enough commonality in nine areas of lower division general education to warrant this universal transfer mechanism called a Passport. The new currency of transfer, therefore, becomes the 63 outcomes memorialized in the Passport experience.

As the New Year opens, we need to think of the students dreaming to succeed as they struggle with the traps and doors embedded in our various systems of higher education; we must continue to innovate and remove unnecessary obstacles. We need to think of the countless faculty and administrators who are willing to rethink the road these students must travel. The work on Interstate Passport has now spanned several years, almost a decade, from its conception to its implementation. It clearly has caught the imagination of many faculty leading for change in higher education. It has been awarded funding by major funders such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Lumina Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York, as well as, a U.S. Department of Education grant. But change in our institutions is hard, as you know, and will require new energy, new commitment and new voices to push this initiative into what constitutes the “norm” of practice. The potential for huge change based on this simple act of acceptance and simplification is monumental to think about. So, we need to rededicate ourselves to the work of innovation and change; a giant leap forward, embodied by Interstate Passport, could become the headline in higher education in 2020. Let’s make it happen together!

Happy New Year from Interstate Passport

As 2019 concluded, I found myself reflecting back on the past year of activities and accomplishments. We welcomed several new schools into the Interstate Passport Network, expanding its membership to 32 institutions spanning 14 states across the nation. Network member institutions awarded 12,786 Passports to students during AY 2018-19. Throughout the three years of operation, 38,886 students have earned a Passport.

As 2019 concluded, I found myself reflecting back on the past year of activities and accomplishments. We welcomed several new schools into the Interstate Passport Network, expanding its membership to 32 institutions spanning 14 states across the nation. Network member institutions awarded 12,786 Passports to students during AY 2018-19. Throughout the three years of operation, 38,886 students have earned a Passport.

Staff and member institution representatives presented on Interstate Passport at multiple state, regional, and national conferences and meetings, including several regional accreditor annual conferences. Working committees met throughout the year to share best practices and provide first-hand perspective on how Interstate Passport is working for students on member campuses. The feedback gained from the committees serves us well by helping to refine our products and processes to better administer the program.

The Interstate Passport Briefing included several interviews with leading experts including Debra Bragg, director of Community College Research Initiatives at the University of Washington, and Richard Detweiler, founder of HigherEdImpact. In addition, the webinar by Doug Shapiro, executive research director of the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, provided very instructive information on the transfer landscape in the U.S.

Looking toward 2020, the primary goal is to expand membership of the Network operating on our four guiding principles of being student focused, faculty driven, allowing for institutional autonomy, and built-in quality assurance. We are currently accepting new memberships and would be happy to meet and further discuss the benefits of Interstate Passport with any interested state or institution.

Staff and member institution representatives will have continued presence at state, regional, and national meetings and conferences including the National Institute for the Study of Transfer Students (NISTS), American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU), The League for Innovation in the Community College, and the WASC Senior College and University Commission. Staff will host select webinars and also have an article that will be featured in an upcoming publication of Change Magazine, with more opportunities to come!

Our Passport Review Board meets at the end of January for its annual meeting and to review and approve the Annual Report, which includes an in-depth analysis of the post-transfer Academic Progress Tracking data submitted to the National Student Clearinghouse. After three years of full implementation and reporting the data are yielding positive results. I am happy to report that the preliminary analysis indicates that students who transferred with a Passport earned an average GPA of 3.48 as compared to 2.93 for students who transferred without a Passport. And the average semester credits taken by students who transferred with a Passport was 11.25, compared to 10.36 credits for students who transferred without a Passport. More details to come on these exciting results!

On behalf of the Passport Review Board and Interstate Passport staff, I wish you all a happy and prosperous New Year in 2020!

Sincerely,

Anna

Anna T. Galas

Director of Academic Leadership Initiatives and Interstate Passport

In the News

Interstate Passport representatives attended the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges’ Annual Conference on December 7 in Houston, Texas. Director of Interstate Passport, Anna Galas, R. Joel Farrell, Air University, and Michael Torrens, Utah State University, presented Interstate Passport: Learning Outcomes Solution to Credit Loss in Transfer.

Interstate Passport representatives attended the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges’ Annual Conference on December 7 in Houston, Texas. Director of Interstate Passport, Anna Galas, R. Joel Farrell, Air University, and Michael Torrens, Utah State University, presented Interstate Passport: Learning Outcomes Solution to Credit Loss in Transfer.

Interstate Passport from an academic advising perspective

Nathaniel (Nate) Pyle serves as the director of academic advising for the University of Arkansas Community College-Batesville (UACCB), and he serves on the Interstate Passport Academic Advisory Committee. UACCB is currently the only Network institution in Arkansas and Nate tells us that the philosophy of Interstate Passport is very much a part of the institution. The University of Arkansas System is in the midst of upgrading the administrative functions for all institutions, so UACCB is incorporating Interstate Passport into this process. The leadership at UACCB takes it very seriously – Interstate Passport has opened up a conversation on transfer and transfer culture.

Nathaniel (Nate) Pyle serves as the director of academic advising for the University of Arkansas Community College-Batesville (UACCB), and he serves on the Interstate Passport Academic Advisory Committee. UACCB is currently the only Network institution in Arkansas and Nate tells us that the philosophy of Interstate Passport is very much a part of the institution. The University of Arkansas System is in the midst of upgrading the administrative functions for all institutions, so UACCB is incorporating Interstate Passport into this process. The leadership at UACCB takes it very seriously – Interstate Passport has opened up a conversation on transfer and transfer culture.

Perhaps the most significant outcome of Interstate Passport at UACCB is a consistent philosophy among advisors and faculty: they no longer look at just giving a student an AA degree but rather providing a skill set that can move students toward a BA. Interstate Passport has been transformative for UACCB to look beyond its own doors. Ideally advisors will try to identify, as early as possible, what a student’s intentions are and build them toward that. And while typically it was assumed that UACCB transfer students would remain in Arkansas, earning Passport offers students the opportunity for hassle-free transfer to other states.

Students at UACCB are predominantly first-generation, low-income students with close to 60 percent of them eligible for Pell grants. UACCB is providing the resources and support to instill – perhaps for the first time for many students – the sense of accomplishment in earning a Passport or an associate degree. Nate described a type of student who may have been “stringing along” in community college for a while with not much to show for it. With a Passport, though, there is power in being able to recognize that they have achieved something. A Passport does represent a milestone.

UACCB has just begun to issue Passports to its students this past academic year. And the Passport Block fits well with the school’s established academic pathways. Two other institutions in Arkansas have expressed interest in joining the Interstate Passport Network; staff will continue to help assess their readiness.

Prior to serving as director of academic advising at UACCB, Nathan Pyle served in higher education roles including community relations, institutional advancement, academic affairs, TRIO Upward Bound, and housing. Pyle holds a B.A. in history from Lyon College in Arkansas, a M.Ed. in higher education administration-public policy/institutional advancement from Vanderbilt University, and is currently working on a doctorate of education in higher education administration from the University of Arkansas-Little Rock.

Transfer Facts: State Policies on Transfer and Articulation

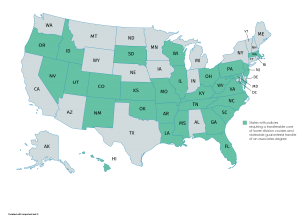

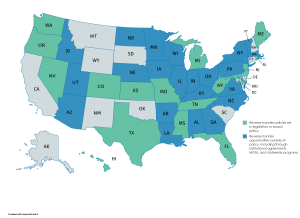

According to the Education Commission of the States 50-State Comparison: Transfer and Articulation Policies report.

- At least 30 states have policies requiring a transferable core of lower-division courses and statewide guaranteed transfer of an associate degree.

- 17 states have reverse transfer policies set in legislation or board policy.

- An additional 22 states provide reverse transfer opportunities outside of policy, including through institutional agreements, MOUs and statewide programs.

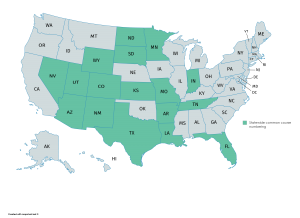

- Only 17 states have statewide common-course numbering used at all public postsecondary institution for lower-division courses

The report notes that many states are refining statewide transfer policies, which suggests a commitment to increasing student completion rates.

The report compares all 50 states in four transfer metrics: (1) transferable core of lower-division courses; (2) statewide common-course numbering; (3) stateside guaranteed transfer of an associate degree; and (4) statewide reverse transfer. The document presents tables showing how all states approach these policies as well as individual state profiles.

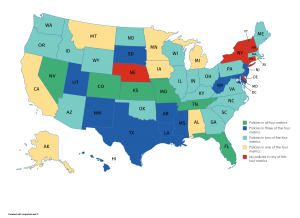

Six states have policies in all four metrics: CO, FL, KS, MO, NV and TN; and six states have no policies in the four areas: CT, DE, NE, NH, NY, and VT. The rest of the states have some but not all of the policies in statute, sometimes because of more than one higher education system within the state, i.e., different system policies, or because of non-alignment with the community college system. In many states, even if a transfer policy is not in statute, agreements are in place between specific institutions or systems within a state that permit transfer of lower-division courses, reverse transfer, or guarantee transfer of an associate degree.

50-State Comparison: Transfer and Articulation Policies

Education Commissions of the States, 2018

Focusing on transfer and transfer students

Rethinking higher education through the consortia model

by John C. Cavanaugh, Inside Higher Ed, October 23, 2019

This article from Inside Higher Ed offers the consortium model as one solution for ensuring seamless transfer – essentially a mini Passport network among a small number of institutions within a state or geographic region. The author describes the problems faced by transfer students as a result of inefficient policies and/or practices – loss of credit, increased tuition costs, and often a sense of despair. As all Interstate Passport members can attest, trust between participating colleges and universities is paramount to the successful implementation of a new model that ensures smooth transfer with acceptance of credits for completed coursework.

How to make room for 100,000 more college students in California without major construction

by Larry Gordon, EdSource, October 24, 2019

This article from EdSource reviews a recent report from the College Futures Foundation on the dilemma facing California: how to serve students in the face of a significant capacity shortfall. The report projects that by 2030 as many as 140,000 students may be turned away from the state’s two public universities because of lack of space. The College Futures Foundation recommends maximizing current assets and resources now, and urges institutions to concentrate on short-term and inexpensive fixes to make more room for students such as better counseling to help students finish faster, more hybrid programs that combine online and on-campus classes, expanded year-round operations, and using available space in community colleges or even high schools to teach bachelor’s degree courses.

The full report is available from the College Futures Foundation here.

Study spotlights outcomes for community college transfer students

by Lois Elfman, Diverse: Issues In Higher Education, December 10, 2019

The National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education (NADOHE) reports on a study that shows how attendance at community colleges increases the chance for low-income and underrepresented students to attend selective four-year institutions. “When comparing minority, low-income and academically underprepared students who directly entered four-year institutions with students of similar backgrounds who went first to community colleges, the students who transferred from community colleges were 24 percent more likely to attend a selective college or university.” Such students bring diversity to four-year institutions, and in addition to lower costs, community colleges offer smaller class sizes and support systems to students. Moreover, the positive impact of community colleges on the successful transition to senior colleges can be used to change the mindset of society.”

Mixing in online courses boosts outcomes for CC students

By Dian Schaffhauser, Campus Technology, December 5, 2019

This article in Campus Technology offers a useful review of a study on the effects of online courses on degree completion, transfer and dropout among community college students. The study focuses on students at the State University of New York. Researchers sought to investigate the “tipping point” at which the proportion of online course enrollment leads to impaired degree completion. Results show that online course completion significantly improves the odds of earning a degree, although racial minorities had reduced outcomes. The report on the study itself, which is very technical, appears in the Online Learning Journal

Tips from the Network